Productivity and wealth are both powerful aids in enabling flow.

But we need to keep these in their place, as a means to an end: Freedom.

If you must do a great deal of work that is unsatisfying and dreary, you are poor.

If you can do only what you love, you are rich.

There is no other definition that matters.

We can achieve this for every one of us, but we must first change our beliefs and our mental models…

Work: a Relic of the Industrial Age

“If it was fun, they wouldn’t call it work.”

All this talk about “doing only what you love” sounds naive.

But it only sounds naive in contrast to the dogma instilled in our consciousness over the last 100 years. In the era of mechanization, assembly lines, and rote memorization, it was naive to hope that both industry tycoon and factory worker would be doing only what they loved.

Today, a massive volume of rote & repetitive work is delegated to machinery, robotics, and software, making more freedom available to human beings. The result? We still spend on average more hours working than at any other time in history. Why?

Unfortunately, while technology has made it possible for us all to be free, the collective institutional mindset has convinced us it is undesirable. We cannot wait for institutions to adapt or evolve. We can be free today, even starting inside the most rigid of institutions.

If you are embedded in this old world, you need to justify doing only what you love, using a reason that speaks to this mindset.

Here is a justification that fits:

Focusing your energy into what you love has a significant side-effect:

extraordinary external results.

The Captain of the USS Benfold

The following story is recounted in both “Good to Great” and “Decisive”. There is no better example of a rigid, control-based, old world institution than the military. And yet, even here, people are finding ways of eliminating drudgery and enabling flow.

In 1977, Captain D. Michael Abrashoff took command of the guided missile destroyer USS Benfold. He immediately interviewed every one of his 311 crew members, asking:

- What do you like most?

- What do you like least?

- What would you change if you could?

Based on this he created two lists. List A had all the critical, important, fulfilling and challenging work. List B contained “the dreary, repetitive stuff, such as chipping and painting.”

“After compiling the two lists, Captain Abrashoff

declared war on List B.”

One of the most dreaded tasks was painting the ship, so one sailor suggested replacing ferrous-metal bolts with stainless-steel ones. The navy didn’t supply them, so crew members actually went down to Home Depot and Ace Hardware and bought every bolt they could find.

A second dreaded task was the scraping and sanding of certain upper parts of the ship, which tended to corrode. The crew discovered a way of protecting the metal from corrosion, but the navy couldn’t handle the volume of metal that needed processing. So the crew tracked down a steel-finishing firm that could do the job for $25,000.

It’s important to pause and note how counter this is to standard navy culture.

After all, the idea that “work must be hard” was born in institutions like the Navy.

Most Captains would see painting, chipping and sanding as a duty fitting for low-ranking crew members. But this war on dreary soul-crushing work paid off, beyond all expectations:

“The sailors never touched a paintbrush again,” said Captain Abrashoff. “With more time to learn their jobs, they began boosting readiness indicators all over the ship.”

With more time to do the challenging and important work that the crew loved, the Benfold crew was able to complete the navy’s standard six month training exercise in the first week, and earned a higher score than any other ship, including those that completed the entire six months.

The Pump vs the Generator

Whether or not you believe it’s possible to do only what you love, you can still make progress by acting as if you believed this already. The next step, then, is to replace your mental model of work with a more complete picture.

The single biggest flaw of productivity systems is that they make it easy to confuse the things you want to do more, with the things that you should do less.

“You don’t make lists of actions and projects just to get them all done and then do nothing else in your life. You process the things you have attention on so you can do what you really feel like doing. And really do it, with 100 percent of your focus and creative energy, with abandon.”

– “Ready for Anything” David Allen, creator of Getting Things Done.

While David Allen understands this completely, the focus of his books and work creates a very compelling picture of half a system. We need a more complete mental model.

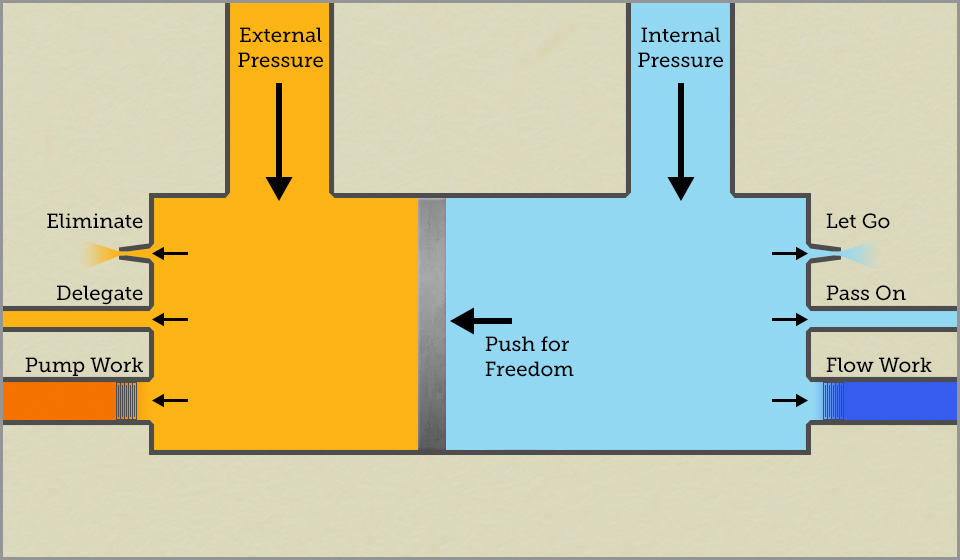

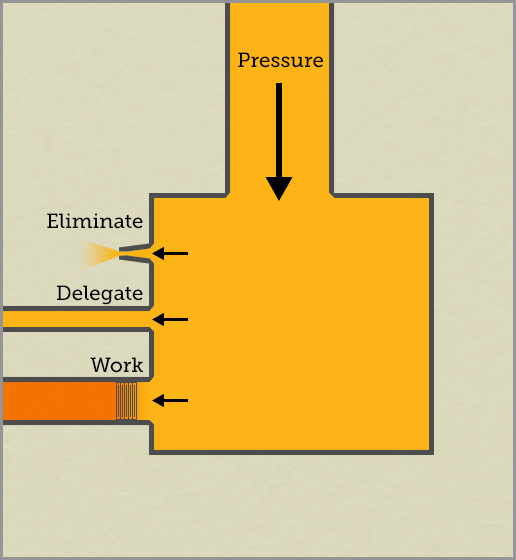

You can think of all the things you want to and need to do, as a kind of pressure.

All tools and techniques of productivity are different ways of moving tasks through this basic system.

Whether it’s internal or external, you can relieve this pressure in one of four ways.

- Reduce the input valve, by saying “No”.

- Vent into the atmosphere, by dropping tasks.

- Pass the pressure on to someone/something else, by delegating/automating.

- Turn the pressure into concrete results, by working.

Separate Chambers

This model works, but it crosses two opposing streams. We know there are different kinds of pressures (internal or external), and different kinds of work (unpleasant or flow-inducing).

When we do work that is unfulfilling, it feels like cranking a hand pump. It is dull, dreary, and drains you of energy.

Intrinsically satisfying activities are different. They are like generators. The more activities you do that pass through your flow channel, the more energy you have.

In order to do only what you love, you first need to create a separation between the internal and external pressures. You need to make your own List A and List B.

Push for Freedom

After creating the separation, you need to redirect some of your internal pressure to reducing the space available to all the things you hate to do.

To do this without excessive stress, you need to equalize the pressure on both sides.

Most productivity systems focus on reducing external pressure:

- Say “No” more often.

- Eliminate anything that doesn’t absolutely need to be done.

- Pass the pressure on by automating or delegating. [1]

The danger is when you try to reduce external pressure by working more. The work pump is your energy biggest drain; you want to minimize the amount of dreary repetitive work you do. The pump is your last resort to relieve external pressure. Don’t make the pump more efficient; just pump less.

They key to making this work, is to also add more internal pressure at the same time:

- Say yes to more things that come up, if you love them.

- Is there anything you’ve stopped doing, that you love and miss?

Start doing these again. - Take back things you’ve delegated or automated, if you love doing them.

You could also certainly increase your internal pressure by not doing anything you love, and devoting all your energy into eliminating that which you hate.

This is the fallacy of delayed gratification, and it’s what turns the journey to freedom into a self-defeating struggle. Your entire goal should be to maximize the flow through that channel, so if there’s one thing to remember, it’s this:

Never stop doing the things you love…

Further Reading:

- [1] If you have trouble with delegating, remember that there is always someone out there for whom the work you hate is the work they derive flow from.

- Mindset: From “To Do” to “Could Do”. I didn’t realize it then, but I was writing about treating the internal and the external differently. I no longer agree on using the “brain-sort” technique for selecting tasks from the “Could Do” tree: intuition works better.

- Decisive. In particular, Chapter 9.3 on the “stop-doing” list.

The post The Pump and the Generator appeared first on Gingko Blog.